Futurismo Ancestral:

Individual Artwork Details

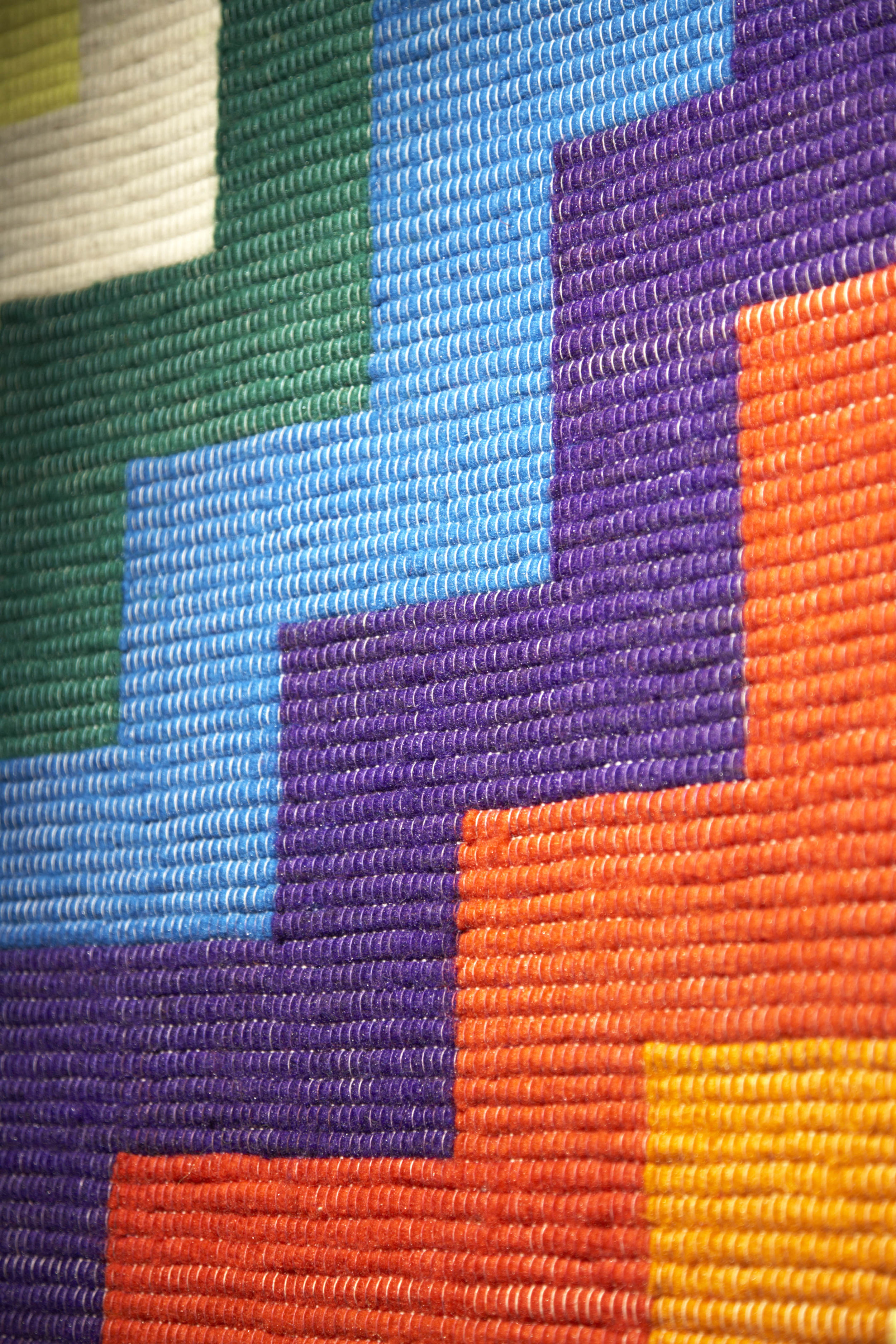

Tapestries

This series of tapestries was made in San Pedro de Cajas, Peru, and in Barcelona, Spain. The designs were based on original geometric shapes, inspired both by the symbolic cues of Andean culture and by the famous Wipala flag: This square emblem, bearing the seven colours of the rainbow, represents the cosmic and social order that maintains harmony between the Qhishwa-Aymara people in both Bolivia and Peru.

70% of the population living in San Pedro de Cajas are involved in craftsmanship, tapestry being the main craft produced in the area. They utilise both flat and hand weave techniques and create their art using sheep wool and alpaca fibres. These tapestries are crafted with exquisite skill and know-how. Their designs embody the technical knowledge of an ancestral culture ranging from the figurative (designs of faces, landscapes from ancient traditions, customs and experiences) to the abstract. The area has been hailed as the Peruvian capital of Textile Art. The local population not only have a strong heritage within weaving culture but show an amazing devotion toward it, producing both tapestries and blankets with sheep wool and natural dyes. They rely on their own herds from which they extract the wool used for the weaving, dying, as well as the background fabric.

The first step of the production of the tapestries was carried out in San Pedro de Cajas under the supervision of renowned master craftsman Luis Nesquin Pucuhuaranga Espinoza. Luis specialises in hyperrealism but is also an expert in a great number of textile techniques. The second stage of the process was completed in my Barcelona studio; here I developed the reverse side of the tapestries, following a logic of accumulative assembly. I used different materials for my compositions: wool hand-dyed with natural pigments, cotton threads of different sizes and colours, and wood strips painted with different patterns. This created different textures and depths as a counterpart to the more symbolic dimension.

My intention with these tapestries was to bridge two worlds, creating an artwork that engaged with both the traditional and the contemporary. It was a practice that, at its heart, speaks of the Cosmos. And one which attempted to reassert the value of the so-called “primitive”, popular arts, coming from a place of pure respect and admiration.

Quipus

On first arriving in Peru, I was made aware of the existence of the artefacts known as quipus (or khipus). I became fascinated by their great beauty as well as by their intricate meaning and significance.

Within the Inca Empire, Quipus were a material device from which both the economic and social aspects of society were recorded. The quipucamayoc (a specialist who elaborated, read and archived the quipus and who had prodigious memories), would record the location, demographic and economic data of a local community, subsequently sending these to the Inca Empire’s administrative centres for collection. Through this, the officials were then able to redistribute excesses of wealth to the less prosperous communities.

Quipus were made of knotted chains of llama and alpaca wool or from cotton. The quantity and position of the knots indicated numerical values in a decimal system. The colours of the cord signified what was being counted, and for each activity (agriculture, military, engineering, etc.) a symbolic system associated with colours existed. Whilst it has been demonstrated that the majority of the information contained in quipus was numerical, there are strong suggestions that these objects also elicited linguistic, lexical information. The quipus thus acted as a form of proto-language, a sign-system in which complex narratives could exist.

With this series of quipus made in my Barcelona studio, I wanted to emphasise the beauty of this great medium of communication. I wanted to show it through a contemporary lens and at the same time to reaffirm a crucial element of indigenous Andean culture. For their production, I used the style of knotting used by the quipucamayoc, however I also incorporated other techniques; for instance, the frayed knots and elements placed upon the cords acted as a reference to the danza de la soga (or rope dance) of the Mochica culture. I also included wooden beads which represent a numerical system using several colours, shapes and linear symbols. The whole quipu is also supported by a fastening bar, something which whilst not overly common in ancient quipus, is an element which has been noted.

Ceramics

This series of ceramics was produced in Nazca, Peru.

The Nazca culture is famous for two things; its vast geoglyphs made in the highlands of the desert, and its culture of ceramics.

Traditional Nazca ceramics were made with the finest clay and polished with great care. Although the shapes they were formed in never had the versatility of those found in the Mochica culture, Nazca ceramics were unsurpassable in terms of their use of colours and pigments, all extracted from local minerals. It is said that the ceramics from this area are the most pictorial and figural of those found in Peru.

I worked in the ceramic workshop of the Gallegos family with the master craftsman Zenon Gallegos. Zenon is the son of the great Gallegos Ramirez, one of the main figures behind the rebirth of the Nazca ceramic technique. For generations, the Gallegos have maintained this millenary know-how inherited from their ancestors. Over the period of two residencies in Nasca, I produced five ceramics following Zenon’s expertise. I worked within the original shape - the oval pitcher with spout handle – using a terracotta plate as a wheel (artesans work without a wheel in numerous areas of Peru). In making these ceramics, I started with the myths of winged beings that permeate many cultures of the ancient world. I used one of the most recurrent characters in my work – this being birds - synthetising this fusion in the beak and evoking the idea of the celestial as well as the lines of Nasca.

After the baking, and following the local tradition, one of the ceramics was offered to the great Cerro Blanco, a sacred mountain of the Nasca culture which is also the world’s highest sand dune. Ceramics offerings have been made to the Cerro Blanco for the past 1500 years. This offering was conducted by Iván Gallegos, a master in many aspects of Andean culture.

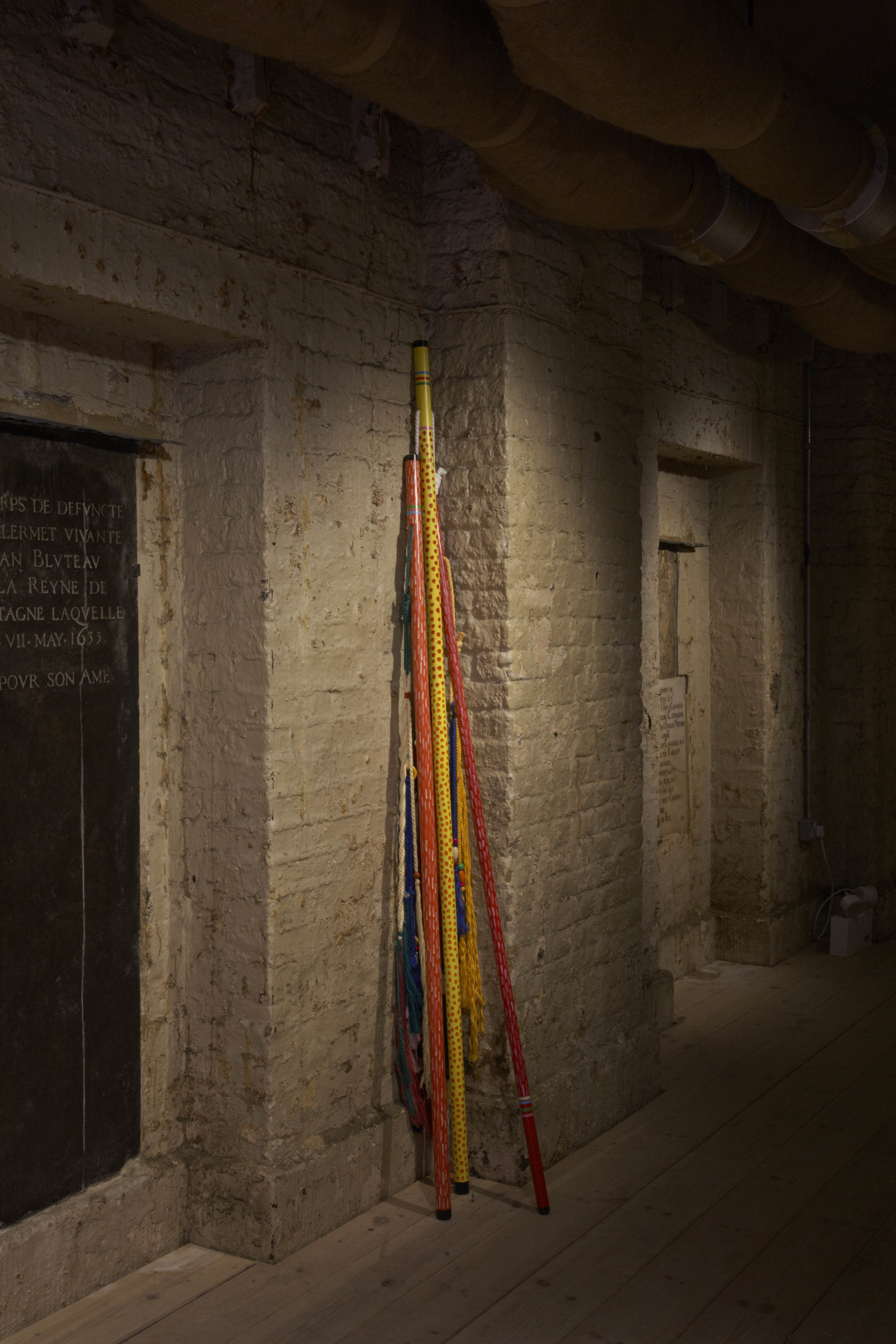

Totems

During my last journey on Peruvian land, I created installations in various regions of the country. The first one was made in the Nazca desert near the ceremonial centre of the Cahuachi. The second installation was produced in the Lurín district (in the province of Lima) near the great temple of Pachacama. Titled Ofrenda Celeste or Celestial Offering, these installations were made in conjunction with the Peruvian artist Valentino Sibadon, more commonly known as Radio.

As a site specific installation, Ofrenda Celeste acted as a mystical game with the cosmos and an interaction with Wholeness. The project started in the telluric vastness of an empty space, in which the totems acted as energy accumulators where multiple manifestations would converge.

The works exhibited here however were produced in Barcelona, using hand dyed wool from Peru. Titled Ídolos or Idols, they are rooted conceptually in my installation project but here introduced into a new space. In this context they thus function as accumulators of offerings. These offerings are made with knotted cords following the same technique used for the quipus, tales of wood made of numbers and linear symbols.

Divided into two bodies, they refer to the world of the celestial and the divine, recreating the sensation of a centre of worship.