Motions of this Kind:

Propositions and Problems of Belatedness

THE BRUNEI GALLERY, SOAS, LONDON

12.4.2019 - 22.6.2019

Curated by Merv Espina, Renan Laru-an

and Rafael Schacter

YASON BANAL - JON CUYSON - LIZZA MAY DAVID & GABRIEL ROSSELL SANTILLÁN - CIAN DAYRIT

MICHELLE DIZON - EISA JOCSON - AMY LIEN & ENZO CAMACHO - KAT MEDINA - MARK SALVATUS

*First institutional exhibition in the UK dedicated to recent contemporary art practices from the Philippines

*Examining “belatedness” and the latency of knowledge between Europe and Southeast Asia

*Newly commissioned works by 11 artists working in or on the Philippines plus a display of materials from the Ifor B. Powell archive

An active research project and research output, Motions of this Kind took place from April to June 2019 at the Brunei Gallery at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. Emergent from a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellowship conducted between 2014-2017, the initial impetus of the exhibition followed 8 months of fieldwork in Manila, the Philippines, exploring contemporary art practice within the region. Taking as its central focus the latency of knowledge between Europe and Southeast Asia, and focussing in particular on our exhibition site itself - the School of Oriental and African Studies, part of the University of London - Motions of this Kind aimed to bring a new focus and wider understanding of art from the Philippines without, crucially, acting simply as another survey show of “art from elsewhere”.

Commissioning new works and developing ongoing projects by 11 artists working either in or on the Philippines – each of whom examine transnational and temporal themes in their practice – as well as featuring a display of materials from the never before exhibited Ifor B. Powell archive held at SOAS, Motions of this Kind charted the historical and contemporary forces linking this archipelagic chain with other key spheres of global power. Placing the theme of belatedness as our principal concern however – as both a concept, reference, and argument – the project underscored the way time has been used both as a weapon of power and a tool of everyday resistance, a way of dominating the marginalised and creating alternative imaginations alike.

As part of the programming for Motions of this Kind we organised Eisa Jocson’s debut performance in the UK, a public symposium with over 10 academic and artists, a workshop by Lizza May David and Gabriel Rossell Santillán, an artist talk with Mark Salvatus, and two nights of films at the ICA, curated by Yason Banal and Amy Lien & Enzo Camacho.

Motions of this Kind has been reviewed in Frieze Magazine, Studio International, Art Review, Spike Art Magazine, amongst others.

Motions of this Kind was curated by Renan Laru-an, Merv Espina and Rafael Schacter. The Foyle Special Collections Gallery was curated by Cristina Juan with support from Delphine Mercier.

Motions of this Kind was initiated and generously sponsored by Mercedes Zobel, partner of Outset Contemporary Art Fund, with support from Philippine Studies, SOAS, and The Office of Senator Loren Legarda. The initiative was made possible by the kind assistance of Approved by Pablo, The British Academy, The British Council, Delfina Foundation, The Department of Anthropology at University College London, Gasworks, and Philippine Airlines.

For our pamphlet designed by Hardworking Goodlooking, please see HERE.

All exhibition videos are by Jhenyfy Muller and all images by Agense Sanvito.

Main Exhibition Text

MOTIONS OF THIS KIND

Propositions and Problems of Belatedness

In Sir Isaac Newton’s treatise Principia (1687), “Leuconia”, the ancient Ptolemaic name of Luzon, the largest island in the Philippines, emerges: “There are two inlets to this port and the neighbouring channels (…) one from the seas of China, between the continent and the island of Leuconia; the other from the Indian sea, between the continent and the island of Borneo”. Laying out the foundations of modern science in his study of motion, universal gravitation, and planetary movement, Newton’s imagistic, at times poetic description of gravitational forces becomes strangely opaque, curiously indeterminate, when discussing the currents surrounding these distant seas. The Philippines is then passing through, appearing now in a universal law.

Centuries later, the Filipino scholar Ricardo Manapat resituated Newton’s text in his study of the sciences and mathematics of Southeast Asia. For him, however, it acted as a vector not simply allowing an examination of the “rise and fall of tides”, but a way to reveal the “historical ebb and flow of ideas" on the “side of the globe farthest from Newton”. This same potency animates the exhibition Motions of this Kind, resurfacing the temporal lag and conceptual fissures in knowledge production and circulation, accessing them through the faculties of art and imagination, and marking them with contemporary mechanisms that shape the Philippines.

Motions of this Kind collaborates with a group of eleven artists intimately connected with the Philippines in order to traverse the historical and contemporary forces that link this archipelago with other key spheres of social, political, and economic power. It carries Newton’s latency of knowledge and keeps the geographic swathe of indeterminacy emergent in his famous text as central to both the methodology and narrative of the artistic and the cultural. Thinking with artists, wrestling with archives, and aspiring/conspiring with “neighbouring shores”, the project assembles interventions, mediations, and other acts of making and articulation that present tentative diagrams of movement, relationships with time, and velocities of subjectivity.

Exhibition Design

ARTIST WORKS

Yason Banal

For a long time the glitch remained motionless... and in disbelief!

2019

Installation with multiple video projections, 3D printed acrylic sculptures, tarpaulins, paintings, photocopies, drone, MIFFED Manila-speed publicly accessible WIFI, other elements, and some surprises

Dimensions variable

Refracted in divergent yet interlinking ways, Banal’s project continues his ongoing exploration into abstract and architectural mechanisms as well as the effects of state power and spectacle.

Whilst comprised of various strands, the work centres around the Marcos-era architectural wonder and nightmare that is the Manila Film Center, built for the so called “New Society” during the Marcos’s three-decade reign in the Philippines. Hastily constructed to provide a venue for the first Manila International Film Festival (MIFF) in January 1982, hundreds of construction workers are believed to have been buried within its walls, as structures collapsed amidst rain and wind during the typhoon season of 1981 and solidified in quick dry cement. Unravelling its haunted history and mythology of pageantry and power, corruption and death, stardom and surveillance, cultural patronage and undead labour, the trajectories and afterlives of the Manila Film Centre are thus made manifest by Banal through elements ranging from video, painting, text and sculpture.

Another core aspect of the work explores the ways in which media is consumed in the Philippines today, specifically through the internet. Slowing the WIFI in the Brunei Gallery down to 1MPBS – accessible to the public through his MIFFED network (password MIFFED19) – this replicates the internet speed of the Philippines, reportedly the slowest in Southeast Asia. Following what he terms the “Quasinternet”, a concept emphasising both the “lack of internet access and slow WIFI frequency” as much as its “homonormative and homonationalist content, from online censorship and poor translation to post-facts and outsourced digital labour and desire”, Banal explores the buffering architectonics and belated dark technology present in this local context in relation to the spectres of MIFF and the Manila Film Center itself.

Jon Cuyson

Dancing the Shrimp (whodoyouthinkyouare?)

2019

Multivariable installation with paintings, found objects, sculpture, sound, drawings, and text

Dimensions variable

The altitude of bruteness moving against the depth and force of the ocean was initially captured in Jon Cuyson’s Kerel (2015), a film proposal fragmented into overlapping forms and media that resurface Genet’s and Fassbinder’s Querelle from and into the body of a Filipino seafarer. The same torso reappears, multiplied and frozen in an archival image of Filipino immigrants in a fishing village in 19th century Louisiana. Two pictures reveal the skill and reflex of ordinary men’s extremities: Kerel’s hand with AK47 and the migrants’ feet with shrimp shells. Both depiction and documentation of agility and adroitness form Jon Cuyson’s ongoing study of (male) subjectivity in spaces and temporalities afforded to the postcolonial.

The new scenography continues to render Dancing The Shrimp as a transnational and modular tableaux through the paternal heritage of British military occupation in Manila. In this new commission that appropriates the popular show Who Do You Think You Are?, Cuyson traces his filial links with an English military personnel, who was drafted in the Philippine capital and later stationed in the neighbouring province of Pampanga, where the artist grew up next to a now repurposed US military base along the contested West Philippine Sea. Dancing The Shrimp (whodoyouthinkyouare?) stages the artist’s tactical test of paternity as an assembly of “echoing references and correspondences” that visually renders objects into a biography of fictions and a personification of histories.

In circumventing genealogical investigation, Cuyson’s Dancing The Shrimp (whodoyouthinkyouare?) smuggles a concurrent contaminant to the valorised conception of filial connection as a source of solidarity and history, and to the legacy of strength—associated with maleness—as a forefather of resistance and emancipation. This critico-fictional import twists into tangents of the postcolonial and the modern: a remix of audaciously camp male transitioning to figures and references capable of torturing old meanings and conceiving new narratives.

Lizza May David & Gabriel Rossell Santillán

How many seas will you swim?

2019

Installation with single-channel video and wallpaper

26’36”

Produced, directed and edited by Lizza May David & Gabriel Rossell-Santillán

Herma Alparaque (voice of Gabriel’s letter), Sebastian Bodirsky (color correction / editing), Jochen Jezussek (sound design)

Inspired by chants and myths from Mexico and the Philippines, How many seas will you swim? displays David and Rossell Santillán’s ongoing exploration of the ocean as a spatial dimension and relational point of view.

Trailing through the Brunei Gallery site – starting within the Foyle Special Collections Gallery, moving down the gallery staircase before situating itself in a darkened cove under the stairs themselves (on levels 0 and -1) – the artists follow traces of the Bauhinia orchid tree, using it to speculate upon trade relations during New Spain.

Bridging the natural with the spiritual, among the many tropes they explore is the figure of the Binukot, a noblewoman and spiritual guide of the Panay Bukidnon people in the Visayas region of the Philippines. Mysterious, as they are secluded from the common folk, the Binukot are first chosen among the most beautiful offspring of the nobles, then hidden from the sun, their feet not allowed to touch the ground. Binukot are tasked to memorise the genealogy of their families and commit to memory the traditional folklore only handed down from generation to generation by spoken word. Only the Binukot have the honour of memorising and retelling these epic songs and stories as they have no written form. The Binukot are living vessels to their peoples' histories, embodying memory, becoming archives.

Working from their own artistic and cultural backgrounds – David from the Philippines and Rossell Santillán from Mexico, yet meeting halfway as art students in Germany – their installation intuitively follows visual appearances, indigenous stories, archival materials, daily news and dream-like states, in order to sketch a dispositif for alternative knowledge and unravelling multi-layered concepts of time.

Cian Dayrit

Northern Conquests in Oriental Soil and Sea

Tapestry, archival objects and documents arranged in museum vitrines

2019

215 cm x 238 cm,dimensions variable

Produced in collaboration with Henry Caceres and Karin Beharrell of Hand and Lock

Commissioned with the support of Gasworks

Dayrit’s map, entitled Northern Conquests in Oriental Soil and Sea, aims to literally upturn our traditional perception of geographic space. Based upon a work from 1744 by Emanuel Bowen (a renowned English map maker who worked for both George II of England and Louis XV of France), Dayrit’s Northern Conquests not only physically reverses the original through rotating the North and South axes, but replaces the colonial names delineated in Bowen’s “new and accurate map of the East India Islands” with the collective names of local indigenous groups. As such, whilst geographically depicting the exact area described by Isaac Newton in the passage from Principia so central to this exhibition – the seas between “Leuconia”, South China, and Borneo, the very site in which Edward Halley’s strange tidal motions were discovered – Dayrit rejects the naturalised efficiency of colonial cartography and instead reveals a defiant minor narrative working against the historical grain.

Yet the power of Dayrit’s “counter cartography” not only emerges via what he sees as their dense infographic status, their ability to function as visual forms depicting space, memory, and time (alongside the plethora of emblems and clandestine insignia he embeds within them), but so too through their basically anachronistic positionality: The contrast of materials, concepts, and temporalities, as well as the chronological juxtaposition of pre- and neo-colonial artefacts (as seen too in his adjacent vitrine installation), thus enables Dayrit to “talk about the issues of today with the language of yesterday” whilst simultaneously critiquing the compromised authorship and content of the traditional map. Moreover, while the main body of the tapestry was produced in Metro Manila, several final key elements were completed at Hand & Lock, a London based establishment founded in 1767 acting as official embroiderers to the Royal Family and Royal Armed Forces. Imperial and colonial history thus not only exist representationally or conceptually within Dayrit’s map but are woven into the very fabric of the tapestry

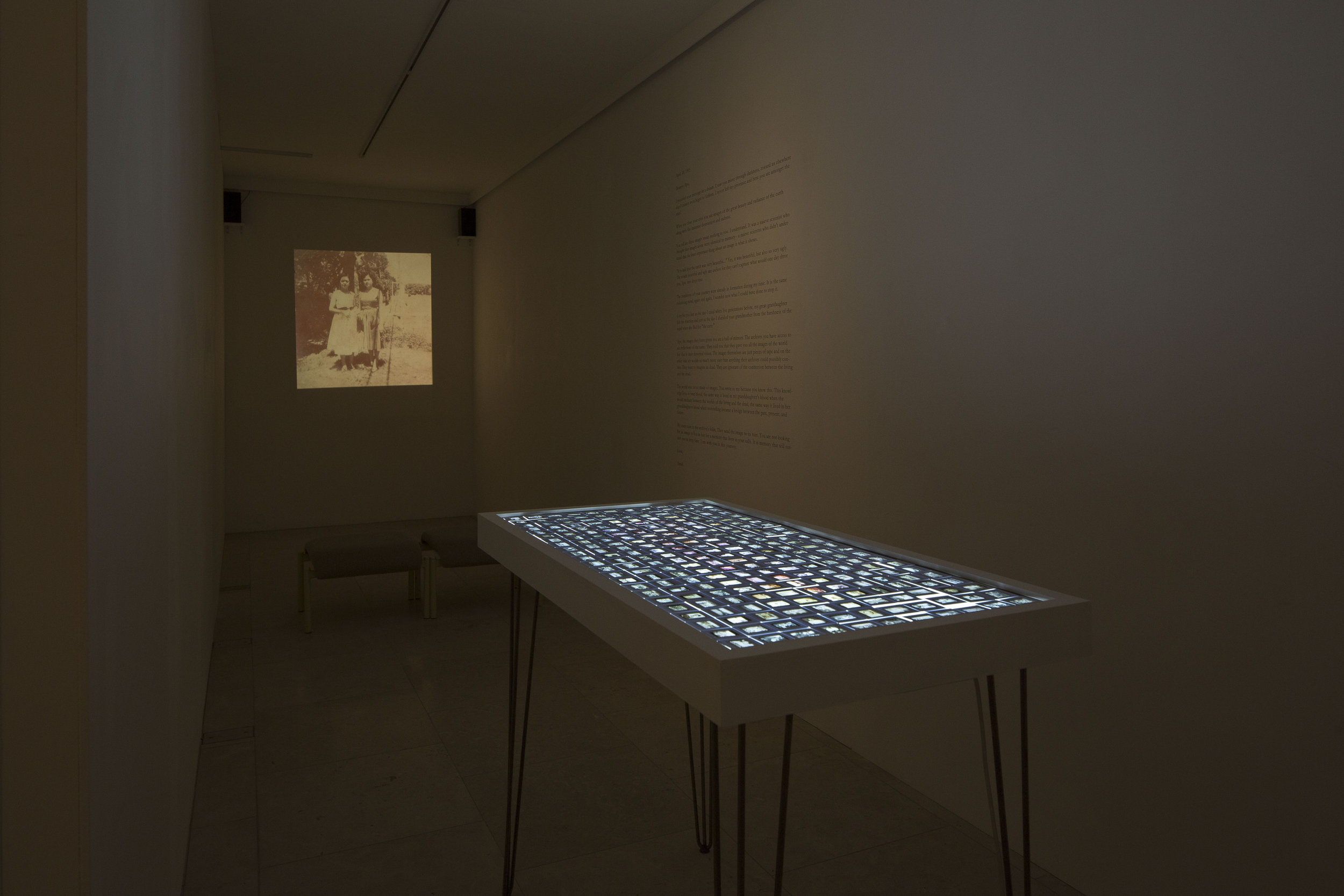

Michelle Dizon

The Archive's Fold

2018

Multi-image slide, digital video, and sound installation with texts

Prophylactic procedure introduces history of cure into a body through its meditative and preventive act. Disinterested in the palliative, Michelle Dizon’s long-term research on US colonial archives resembles a walkthrough in an infirmary of remediation, reparation, and restitution. These terms are chronic yet futural: Images and documents are nurtured in her study of violence, locating them into the specificities of globalisation and migration and risking these visualities into the potency of intimate spaces of resistance.

The sickness of the archive, its ruins refusal to collaborate further, and its current placement in a planetary scale of destruction emerge in Dizon’s sensitive attention and mediation in her recent work titled The Archive’s Fold. She organised an installation of images and sounds based on a correspondence between her great-great-grandmother in 1905 and her imagined descendant in 2123. Both named Latipa: The former writes about surviving with images, and the latter writes about surviving for images. Both daring to live and dream in different spatio-temporal constructions of darkness. Their intersectionality lies at the cross-section of a fold: US colonial photographs are now summoned by images of women in Dizon’s family album, who are migrants of Chinese heritage in what used to be a predominantly Muslim empire of Cotabato in the south of the Philippines. This trans-temporality cultivates meanings in the archives.

As Dizon produces duration in a textual intervention of the archives, and claims space in a pictorial calibration of the same holdings that monumentalise violence; she allows the archival to speak again, its pictures to run amok across aspirations and imaginations. This custodianship as artistic practice nourishes the formerly infirm, abused, and absent as faculties who talk back, return the gaze, and sustain difference. It is generous and caring and therefore, refusing to be worn out.

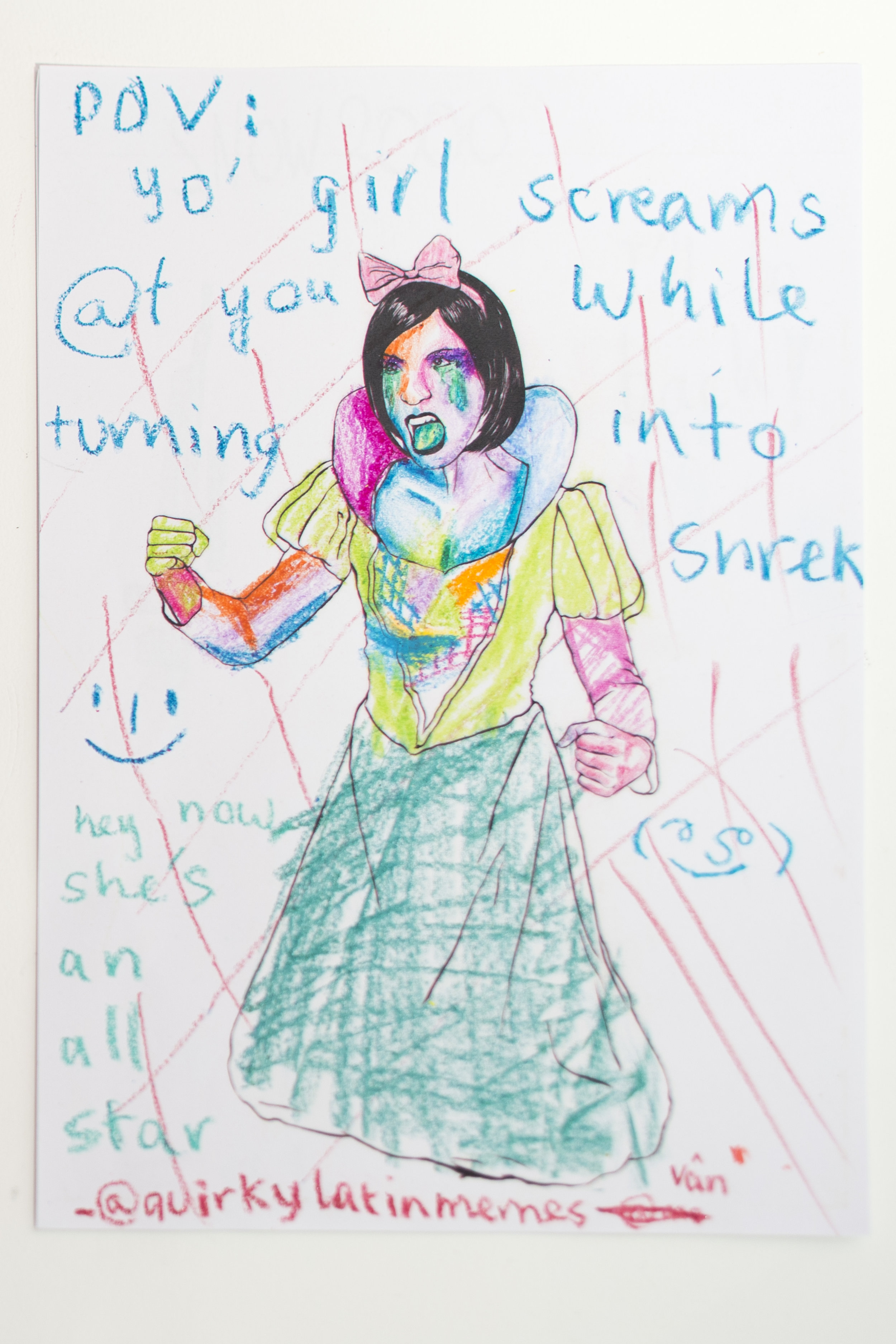

Eisa Jocson [Exhibition Install]

Becoming White

2019

Video documentation of public intervention. Framed A4 and A3 coloured copies from Manila and Shanghai . Photocopies for the audience to take and colour

Produced for Cultural Center of the Philippines' 13 Artists Awards 2018 and Bangkok Art Biennale 2018

In Disneyland Hong Kong, a legion of dancers from the Philippines are employed as professional entertainers to repeat formatted performances of “happiness” as their daily labour. Excluded from the main roles that are reserved for specific racial profiles, they are assigned anonymous supporting parts such as a zebra in Lion King, a coral in Little Mermaid, a monkey in Tarzan. Becoming White points to a deeply embedded colonial construction that directly manifests in migration, labour opportunities and the daily performance of happiness of Filipino workers in the service industry – from professional dancers in Disneyland to nurses, nannies, and domestic workers elsewhere.

Emerging from Jocson’s ongoing Happiness series, a project that probes into the system of desire formation within the global Disney entertainment empire, Becoming White unpacks the process of two Filipino performers hijacking the figure of Snow White through a detailed reconstruction of a powerful symbol of Happiness: The Princess, the archetypal model that dominates the narrative imagination of children while excluding their context, bodies and histories. These problematics are constructed in a performance, embodied by Jocson and collaborator Joshua Serafin, seen here as a video documentation. The installation also includes documentation of Jocson’s Isnowhite Procession, a parade-of-sorts from the Cultural Center of the Philippines in 2018 to a Chinese fast food restaurant in front of the US Embassy (along historic Manila Bay) as well as her participatory colouring activity series Colouring White. Inviting the audience to take a page and colour-in to add to this ongoing project, here the work’s previous iteration at the Cultural Center of the Philippines in 2018, in which the works unexpectedly acted as a message board, are shown here.

Eisa Jocson [Performance Work]

Amy Lien & Enzo Camacho

Notes on “The Angry Christ”

2019

Charcoal, real/imitation blood, molasses, semen, and soil

Dimensions variable

Amy Lien and Enzo Camacho’s work departs from a remarkable church mural on the Philippine island of Negros commonly known as The Angry Christ. Painted in 1950 by the New York-based, Filipino-American artist Alfonso Ossorio, this wild depiction of the Last Judgment adorns a chapel that was built to service the workers of an industrial sugar refinery. Both the refinery and chapel are still in use today.

Notes on “The Angry Christ” consists of fragmentary research notes transcribed over charcoal tracings of the mural on several walls in the gallery’s light-saturated upper stairwell. By engaging the act of copying as a mode of close study and interpretation, Lien & Camacho utilize the formal density of Ossorio’s original mural as a structural tool, allowing them to sketch out a lush cosmology that encompasses narratives of queerness and Modernism, Catholicism and Communism, oligarchy and sugar, which spiral outward from the The Angry Christ and its regional context. By following these threads forward into the present and tying them to live political struggles, the artists ask how The Angry Christ might be radically reprogrammed towards collective expressions of anger in our contemporary moment.

Alongside this mural is a new series of drawings on handmade paper embedded with various organic matter gathered in Negros—including sugarcane pulp sourced from the same sugar mill complex that is the site of The Angry Christ. This bio-matter is enmeshed with a wax-resist technique that Ossorio utilized in a series of drawings he made while working on the mural, which embodied a private perversity that couldn’t be expressed in the sacred space of the church. The drawings have been unpacked and repacked, worked and reworked, on their journey from Negros to London, via Hong Kong and Manila, tracing the exigencies of the artists’ peripatetic movements. Presenting this project here in London draws the specificity of The Angry Christ into the global metropolis, underscoring an urgency to acknowledge those overlooked spaces which bear the harshest wounds from capitalist circulation.

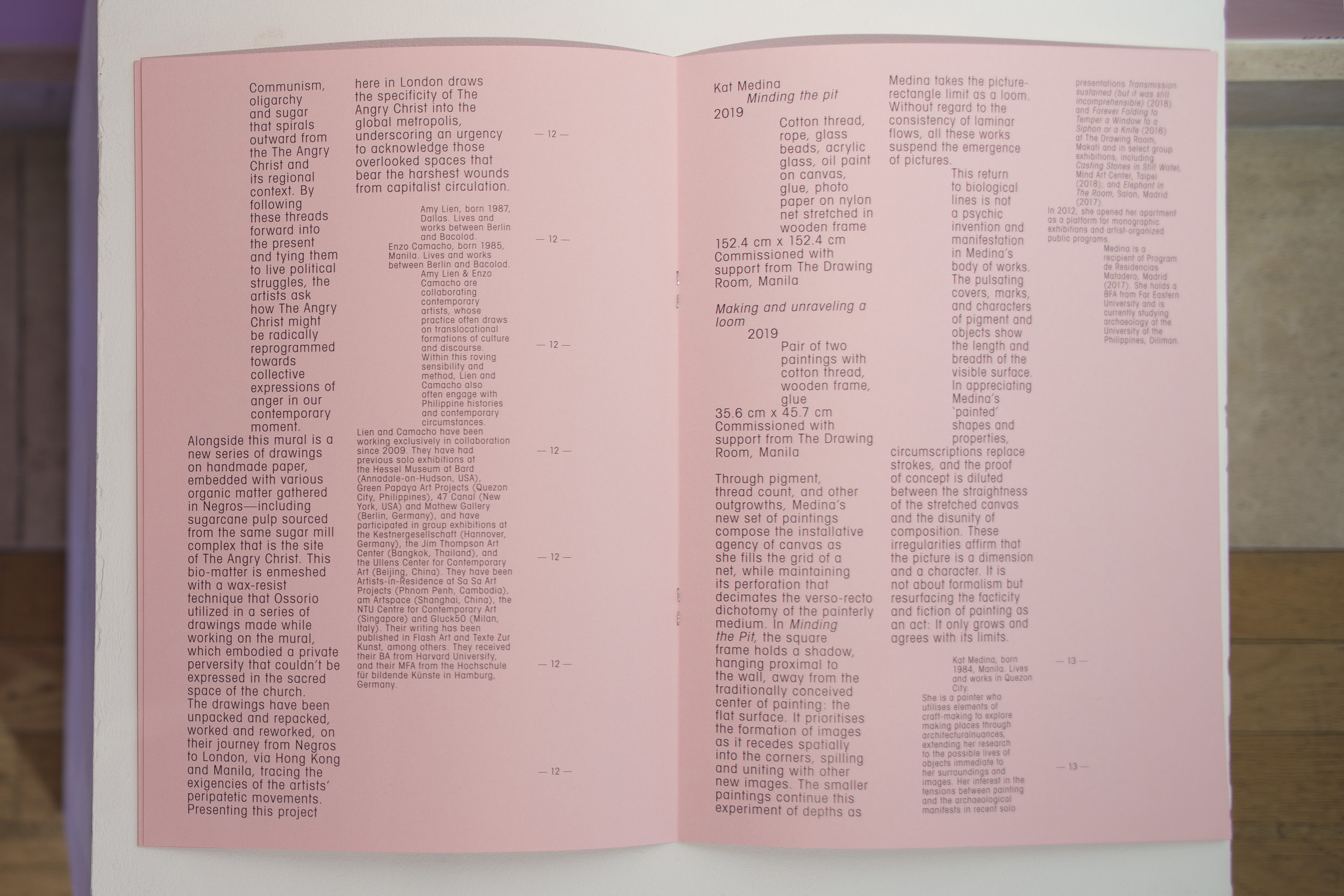

Kat Medina

Minding the pit

Cotton thread, rope, glass beads, acrylic glass, oil paint on canvas, glue, photo paper on nylon net stretched in wooden frame

152.4 cm x 152.4 cm

Commissioned with support from The Drawing Room, Manila

Making and unraveling a loom

Pair of two paintings with cotton thread, wooden frame, glue

35.6 cm x 45.7 cm

Commissioned with support from The Drawing Room, Manila

Abstraction’s readability is never accessed through poverty, crudeness, and unreliability of materials. And perhaps this evasive intelligibility caused by the same class of elements produce the tenability of abstract. Applied to Kat Medina’s practice, predominantly articulated in the concreteness and finality of craftmanship, the indices of making the figurative and abstraction terminate abruptly at the drifts and morphologies of the materials she uses. It remains in the discourse of painting, endowed with thickness, erasure, and motility.

Through pigment, thread count, and other outgrowths, Medina’s new set of paintings compose the installative agency of canvas as she fills the grid of a net, while maintaining its perforation that decimates the verso-recto dichotomy of the painterly medium. In Minding the Pit, the square frame holds a shadow, hanging proximal to the wall, away from the traditionally conceived center of painting: the flat surface. It prioritises the formation of images as it recedes spatially into the corners, spilling and uniting with other new images. The smaller paintings continue this experiment of depths as Medina takes the picture-rectangle limit as a loom. Without regard to the consistency of laminar flows, all these works suspend the emergence of pictures.

This return to biological lines is not a psychic invention and manifestation in Medina’s body of works. The pulsating covers, marks, and characters of pigment and objects show the length and breadth of the visible surface. In appreciating Medina’s ‘painted’ shapes and properties, circumscriptions replace strokes, and the proof of concept is diluted between the straightness of the stretched canvas and the disunity of composition. These irregularities affirm that the picture is a dimension and a character. It is not about formalism, but resurfacing the facticity and fiction of painting as an act: It only grows and agrees with its limits.

Mark Salvatus

Blue Moon

Video installation in single channel with masks, vinyl, and LEDs.

8’, dimensions variable

Produced by Salvage Projects

On December 31st 1910, in Salvatus’s home town of Lucban in Quezon Province, a masquerade took place to “pay tribute”, as a local newspaper reported, “to the year that had just ended”, a “simple experiment” that the townsfolk wished to turn into an annual event. Intended to provide “proof” of the town’s “exquisite taste and love for riots and expansion”, the Lucban Carnival of 1910 was, however, realised just a single time, almost entirely vanishing from social memory and remaining unrecognised for the following 100 years. Discovering an image of the carnival and the newspaper article in question within the archive of the Lopez Museum and Library in Manila however – part of which features prominently in his installation – Salvatus decided to return to Lucban to re-enact this historical moment, a belated reprisal (just 108 years late) reanimating this uncanny, perplexing, yet beguiling event.

Yet key questions still remained for Salvatus. Who in fact introduced the masquerade into Lucban? Who influenced its style? What was the exhibition or festival the participants said that they wanted to display alongside it? At a key transition period between Spanish and American colonization, between the religious Catholic pageants brought from Iberia and the more secular parades brought from the States, the newspaper images at first seem simply to show elements of the both. Yet the conquistador-style features depicted on many of the masks also reveals a wider link to Mexico, the colonial administrators of the Philippines during the rule of Spain. As such, this very local, seemingly parochial event can be seen as an opening from which one can enter much wider, global networks. Like much of his work, Salvatus thus not only pays tribute to his ancestors and their vernacular, participatory, creative actions, but connects the periphery with the centre, the minor with the major, the actions of the street with that of the State: The history of his hometown, of his family, thus becomes subtly intertwined with our all encompassing metanarratives, history from below reclaimed to the status of the truly Historical.

Cristina Juan & Delphine Mercier:

Para-curatorial archival installation

Informal Empire: Philippine-British Entanglements until the 19th century

Archival display

2019

Commissioned with support from Philippine Studies, SOAS, and UCL Anthropology.

Courtesy of SOAS Library, UCL Ethnographic Collection, and Sir Richard and Lady Hyde Parker of Melford Hall, Suffolk

Curated by Dr Cristina Juan with the support of Delphine Mercier, Informal Empire: Philippine-British Entanglements until the 19th century is an archival complement to the exhibition.

Selecting material from the Ifor B Powell Collection held in the SOAS archives, the exhibit uses the historiographic concept of Informal Empire to describe the extensive yet shrouded reach of British interests in the region. The Philippines, while not directly ruled by the British except for the brief occupation of Manila from 1762-64, was nevertheless the site of de facto domination in which the British were one of the most active drivers of Philippine economy, trade and even cultural capital in the late 18th to the 19th century. From Ifor B Powell’s extensive field research in the Philippines, where he spent three years as a Rockefeller scholar collecting data in the 1920’s, to his subsequent correspondence with Philippine scholars and life-long proclivity for collecting Philippine-British primary source materials, Informal Empire teases out four emergent themes: the British occupation of the Philippines between 1762 and 1764; the economic and cultural interests of Britain in the Philippines that persisted deep into the 19th century; the British negotiations with the Sultanate of Sulu and North Borneo on behalf of the East India Company; and British vice consul Nicolas Loney’s role in the agricultural sugar production of Negros.

PRESS